On this page you will find information on the:

Banana Spider, Black Swallowtail, Bowl and Doily Dragonflies, Love Bug, Lubber Mosquito.

Banana Spider:

Besides having a weird, long body and eight vile-looking pointy legs spanning four inches, Banana Spiders (Nephila clavipes, a.k.a. Golden Orb) have a habit of putting their webs at face level in the woods. If they manage to survive an unfortunate encounter with an unsuspecting human, they will no doubt carry fond memories for the rest of their year-long lifespan of the human flailing his or her arms around, cursing and doing a spastic, impromptu little dance in the woods. A wise, surviving Banana Spider would best build its next web a little higher off the ground.

They spin a durable, round web of a golden hue, thus the name Golden Orb, that has filaments stronger than steel by weight. In typical spider fashion, they hang out in the center of their web and feel for vibrations from possible victims. If they detect one, they hustle over to subdue it with their venom and drag it back to the center of the web to wrap and store the carcass away from rival spiders.

The spider doesn’t seem to be inclined to bite people unless severely provoked and if it did, it might only cause a little temporary redness. This bite, however, will be death to any flying insect that fails to see the spider’s big web. Small birds and snakes have also been known to blunder into these webs and get this same treatment. One theory supposes guard strands around the perimeter of the web collect leaves and such to act as warnings to keep larger animals from inadvertently wrecking the web. However, if one does get stuck and starts to cry out in a small, squeaky voice, “Help me! Hellllp me!” Mr. Spider will amble over and, under his many-eyed gaze, administer as many venomous bites with his fangs as needed to subdue the guest and try to make a meal of it.

Black Swallowtail:

A pair of Black Swallowtail Butterflies (Papilio polyxenes) flutter madly around each other, making it hard to tell if they’re mating or fighting. The species is, after all, pretty much preoccupied with defending territory or getting hooked up with the opposite sex. As they flit and bump into each other one can figure they are either doing a delicate, poetic aerial ballet set to romantic violin music or just fighting like a pair of sissies. It turns out a closer look makes it pretty easy to tell since the boys have gold dots on the top and bottom of their wings and the girls have beautiful blue hues on theirs.

A good number of Swallowtail’s survive the summer and one might think that a big, black, slow moving insect, lazily gliding around open fields would be an easy target for hungry flying insectivores. Though the Black Swallowtail are non-poisonous and quite edible (to an insectivore), predators avoid them because its appearance mimics that of another big, black butterfly, the Pipevine Swallowtail (Battus philenor), that is toxic. Apparently, most potential predators take no chances and leave both bugs alone.

Bowl and Doily Spiders:

When the morning humidity is just right, thousands of Bowl and Doily (Frontinella pyramitela) spider webs can be seen along the Manchac Greenway drooping with the fullness of the morning dew. They’re easy to spot then but tend to become invisible after the dew evaporates.

The webs are attached to tall grass and shrubs, are about the size of a hand and are in two parts – a bowl shape hovering above a flatter disc shape. To some, the lower part resembles a doily (a decorative lace thingy old ladies used to place under glasses, bowls and plates).

As you know, a spider doesn’t simply stand around waiting for prey, it lurks, and this tiny spider does its lurking in the narrow space between the bowl and the doily. When a gnat, fly or other small insect blunders into the bowl, it finds that it’s not sticky like many other webs and cooperates by sitting still for a moment to take a rest. The spider then trots over and bites the bug from underneath the bowl.

Dragonflies:

They are lords of the air, predators who suddenly swoop down from above to terrorize mosquitoes, gnats, midges and other such small things. Hundreds of them can be seen patrolling areas around the Manchac Greenway in summer.

They possess a certain grace, floating gently about on twitchy, x-shaped wings, sometimes stopping to perch on some high point to regally survey the landscape with their jerky, mechanical 360 degree gaze.

They come in a variety of wild, vivid colors like some sort of psychedelic hallucination: royal blue, red, yellow, gold, powder blue, pink, green and white with bold black stripes.

At the end of their season they do the weirdest thing. There are fewer of them by this time because they’ve spent the summer being someone else’s food – birds, lizards, frogs, spiders, car radiators and even fish get at them and after a while the ones that are left just don’t seem to care. They become docile and will actually buddy up to humans and make themselves available for close inspection. It’s as if they are telling us, “I’m done here. I’ve done my part. Eat me if you want, but I prefer we just be friends.”

Love Bug:

There is not a more worthless creature on the face of the planet than the Lovebug (Plecia nearctica). Thousands of these loathsome, two-headed flies buzz around aimlessly in April-May and August-September on the Greenway and across the Gulf South, preoccupied with nothing but sex and landing all over cars, boats, fresh paint and people. They are of almost no benefit to anyone or anything except the decomposers that deal with their thousands of stinking, dead bodies. (Love bugs themselves were decomposers in their larval form, feasting on decaying leaf matter.)

At least they can’t bite and supposedly only dabble a little nectar and pollen to live above ground for just three days or so (though their swarms can last a month). The female, being the larger of the two, usually leads the coupling couple. She lives longer and gets to drag around a corpse for a day or so.

Nothing much eats them because they are too acidic and it’s this acid that dries and scars the leading parts of vehicles speeding on the highway. Research indicates one reason they hang out on the highways is they are attracted to engine exhaust and fumes. This fascination with fumes is also why they like to get stuck in fresh paint. They also love the color white, which explains why they cling all over white boats, especially those with fuming engines.

This insect is an invader from Central America that crossed into Texas around 1911 and has since spread across the Gulf Coast. It is believed their numbers have been limited by a parasitic fungi, so declare “Hooray for the parasitic fungi! We can’t have enough parasitic fungi!”

Lubber Grasshoppers:

The remarkable size and odious reputation of the Lubber Grasshopper (Romalea guttata) has given them names that are legion: Devil’s Horse, Black Diablo, Graveyard Grasshopper, Giant Locust and in Louisiana French – Cheval Diable.

They get their start in March from clusters of tiny half-inch babies, or “nymphs,” emerging from the ground where Mama laid their eggs last summer. They then spread out and spend the summer discretely devouring the surrounding wetland vegetation to end up being two-and-a half to three inch-long monsters. Some remain black as the devil others develop a yellow pattern and their short, stubby red wings are, thank goodness, useless for flying. They have few predators because nothing much wants to eat them. When threatened, they let out a hiss of complaint and froth a dark, toxic, brown “tobacco-juice” from their mouth that is known to make impetuous raccoons and ‘possums who attempt to eat one to upchuck.

These traits and the bug’s intimidating size gives them no reason to hide; they swagger with impunity and as a result, maintain enough of their number to mate shamelessly out in the open at the end of the summer. They appear in the middle of the Manchac Greenway and on other swamp thoroughfares looking for love and offering themselves for slaughter by automobile in the thousands. When it’s time, a surviving Mama backs her eggs into the ground where they spend the winter as larvae, getting ready to begin their annual cycle next spring.

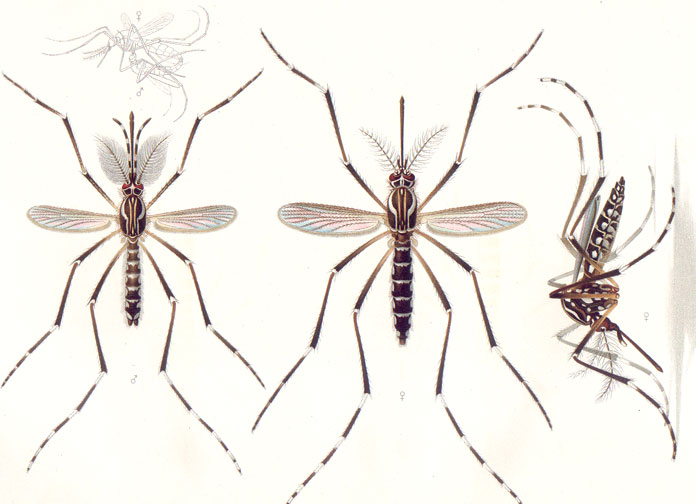

Mosquito:

Mosquitoes can shadow us night or day, waiting for a chance to bite, hovering expectantly about our heads like an annoying halo, though most species prefer to hunt humans and other warm-blooded animals at dawn and dusk. One of the ways they zero-in on us is by sniffing the air for our byproducts – carbon dioxide and body odor. Dousing your body with sharp, repulsive counter-odors to hide your lovely scent will confuse them and make them less likely to bite.

There are fifty-two species of mosquitoes in Louisiana (the most, 44, are in Orleans Parish) and each bites according to the time of year, location, rainfall, temperature, barometric pressure, humidity, wind, time of day, orneriness and other factors. Depending on the species, they may leave a bite that stings when it happens or is undetected until the perpetuator is long gone or leaves large, swollen welts that last half a day or make a deep, exasperating itch or leave whatever that specie’s “calling card” is.

The mosquito Aedes aegypti, with its cute little striped legs, is known in this part of the world for helping kill hundreds of thousands of Louisianans in the 1700s and 1800s by spreading the Yellow Fever virus. The insect makes it a point to be awake and biting during the day when humans are most presentable and is adapted to sloppy human habits like leaving lots of water-filled places amongst our rubble, junk and trash where they can breed. As most mosquitoes travel no more than 150 feet from their place of birth, a little tidiness around the yard will help keep their numbers down.

An interesting video on the Internet shows how each bug carries a miniature hypodermic needle called a proboscis on its business end. They land on the exposed flesh, grab hold of some hair and bow their heads as if in prayer (praying they don’t get caught) and gently, almost tentatively, lower the proboscis. Grotesquely, like a scene from the movie Alien, the proboscis probes into the skin and several fine, pointy tongues sprout from it and twitch nervously between skin cells until one finds a living, pulsing blood vessel and then stabs it to begin diverting the host’s lifeblood to the inflatable, flying tank above. They also spit a little back in to infect the host with whatever virus or bacterium they happen to be carrying that day. They then use the blood they’ve stolen to bring about the miracle of life to their hideous offspring.